Early Germanic calendars were lunisolar, meaning they combined both lunar and solar aspects. In the Runic calendar, the New Year begins with the first full moon after the winter solstice. The first month of the year is Aefterra Geola (After Yule). The last month of the old year begins with prior full moon and was called Aerra Geola (Early Yule).

Early Germanic calendars were lunisolar, meaning they combined both lunar and solar aspects. In the Runic calendar, the New Year begins with the first full moon after the winter solstice. The first month of the year is Aefterra Geola (After Yule). The last month of the old year begins with prior full moon and was called Aerra Geola (Early Yule).

Multiple sources attest to the importance of the winter solstice in determining the New Year. However, it’s less clear as to whether or not Yule was celebrated specifically on the solstice. Since the Germanic calendars were set according to the timing of the solstice, there is a good argument in favor of holding Yule in conjunction with the solstice. However, there are other traditions to consider.

Some claim Yule was a 3-day festival, others cite 12 days, and in Iceland there are 13 days leading up to Yule. Since Iceland was the last country in the region to be Christianized, I’m inclined to accept their 13-day pre-Yule tradition. The other thing to consider is how these traditions fit into the Germanic calendars. If Yule is a 3-day festival, proceeded and followed by two 13-day periods, this amounts to 29 days. That closely approximates the lunar cycle. One lunation is 29.5 days and the months in most pagan calendars alternated between 29 and 30 days.

If we evaluate how this plays out in 2022, we get:

- Aerra Geola (Early Yule) begins at the full moon on 12/7/2022.

- For the first 13 days a different Yule lad arrives.

- Yule begins on the Winter Solstice, 12/21/2022

- Yule ends on 12/23/2022

- For the next 13 days a different Yule lad departs.

- Aerra Geola ends 1/5/2023

- Aefterra Geola (After Yule) and the New Year begins at the full moon on 1/6/2023.

The calendar lines up with the solstice surprising well in 2022, but that is seldom the case. For instance, in 2024 the full moon proceeding the winter solstice doesn’t occur until December 15th. Thus, Yule would not be celebrated until December 29th and the New Year would begin on January 13, 2025.

Regardless of timing, Chapter 55 of the Prose Edda (book Skáldskaparmál) list different names for the gods, one of which is “Yule-beings.” Among his many other epitaphs, Odin also bears the name Jólnir, “The Yule One.”

Yuletide is traditionally connected with the Wild Hunt. During the hunt, Odin leads ghostly huntsmen through both the supernatural and natural worlds in search of their quarry. Unsuspecting mortals who encounter the hunt may be abducted and taken for a wild ride through the blustery winter skies. It is also a time of increased supernatural activity, as draugrs walk the frozen earth.

In Old Norse poetry, the word jol is frequently used interchangeably with feast. The raven is a well-known symbol of Odin and hugins jól translates as “raven’s feast.” This makes sense because Yuletide celebrations were essentially a potluck. Families brought food with them to the feast along with livestock to be slaughtered and eaten there. Conversation flowed freely as people gathered near fires, passing around a horn of mead or ale.

After blessing the meal, the host or village chieftain would offer a series of toasts:

- The first toast was always drunk to Odin “for victory and power.”

- The second toast was to Njordr and Freyr “for good harvest and peace.”

- The third toast was drunk for the king.

Afterwards the tradition of “a toast, a ghost, and a boast” followed. During these rounds of drinking, anyone present could offer a toast.

- The first round toasted the good health and fortune of those present or offered thanks for friendship.

- The second round were toasts for dead loved.

- The third round was boasting about personal accomplishments, followed by toasting yourself.

King Haakon I (934 to 961) brought Christianity to Norway and rescheduled the Yule feast to coincide with Christmas. According to the Saga of Hakon the Good, Yule was originally celebrated for 3 nights beginning on midwinter (the solstice). This is presumably where Yuletide and Christmas customs became intertwined. Many of these traditions still exist today, such as serving a Christmas Ham (Yule Boar, Sonargöltr), displaying a Yule log, and going caroling (wassailing).

Below are some lesser-known Yuletide traditions.

Yule Cat

The trollish Yule Cat, or Jólakötturinn, is a monstrous black cat that lurks through the snowy countryside eating people who did not received any new clothes by Yule. It’s possible that the Yule Cat is the most dangerous creature among all its kin.

The trollish Yule Cat, or Jólakötturinn, is a monstrous black cat that lurks through the snowy countryside eating people who did not received any new clothes by Yule. It’s possible that the Yule Cat is the most dangerous creature among all its kin.

Fear of the Yule Cat kept housewives and servants from idleness. Sheep are shorn in May and June. Over the summer the wool must be washed, dried, carded, and spun. The spun wool could either be knitted in to garments or used to feed the looms and woven into broadcloth.

In the nights surrounding Yule, Grýla and her sons venture from the mountains, striding side-by-side to cause mischief and gobble up naughty children. Their pet, the Yule Cat joins them on these nightly forays, appearing each night only after a household has gone to sleep. It’s nimbleness and stealth enable it slink through buildings and into the bedchambers, where it snatches its victims.

Icelandic poet, Jóhannes úr Kötlum, wrote about the Yule Cat. The original translation was from Vignir Jónsson. I have added minor changes to make it rhyme.

You all know the Yule Cat

A cat that was huge indeed.

No one knew from whence he came

Or where he went with speed.

He opened up his glaring eyes,

The two brightly glowed.

And the sight shook the bravest man

To his very toes.

His whiskers were sharp as bristles,

His back arched up high.

When unsheathing the claws of his hairy paws

Someone was sure to die.

With a wave of his strong tail,

He jumped and he clawed and he hissed.

Sometimes in the valley,

Or through the shoreline mist.

He roamed at large, hungry and evil

In the freezing Yule snow.

And in every house

They shuddered at his name, you know.

If one heard a pitiful “meow”

Something evil would happen soon.

Everybody knew he hunted men.

For him mice were nary a boon.

He picked on the very poor

That no new garments got.

Who toiled and lived in dire need,

In retched squalor and want.

From them he took in one fell swoop

Their whole Yule dinner,

Always eating it himself

Never growing thinner.

Hence it was that the women

At their spinning wheels sat

Spinning a colorful thread

For a frock or a sock to stave off the Yule cat.

Because you mustn’t let the Yule Cat

Get hold of the little ones sitting ‘round your fire.

They must get something new to wear

Or their fate indeed, will be dire.

When the lights come on Yule Eve,

And the Cat peers in,

The children must stand rosy and proud

All dressed up proper and prime.

Some had gotten a new apron on

And others had gotten shoes

Or something dearly needed,

spun from the wool of ewes.

All who got something new to wear

Stayed out of the pussy-cat’s grasp

Then he gave an awful hiss

And was on his way at last.

Whether he still exists I do not know.

But his visit would be in vain

If everybody donned new stockings

The next time he came.

Now you might be thinking of helping

Where help is needed most.

And find some little children

Who need some woolen coats.

Perhaps helping those

Who in a lightless world toil,

Will bring you satisfaction

And a Joyous Yule.

Households can easily rekindle this Yule tradition by reciting the poem and gifting a pair of socks to everyone on their holiday shopping list.

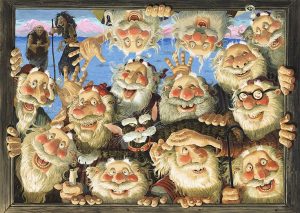

Yule Lads

The Yule Lads are descended from the trolls Grýla and Leppalúði, two of the most hideous ogres ever known. Leppalúði is lazy, so he typically stays home. But Grýla is hideous, inhumanly strong, lustful, and cannibalistic. She is originally mentioned in the Prose Edda in a rhymed verse attached to Snorri Sturluson’s Skáldskaparmál and appears in the Sturlunga Saga. The giantess has an insatiable appetite for human flesh. She can detect misbehaving children year-round, but only comes from the mountains during the winter to searach towns and villages for a meal. Any children she finds are carried home in a skin sack. Her favorite meal is stew of naughty kid.

The Yule Lads are descended from the trolls Grýla and Leppalúði, two of the most hideous ogres ever known. Leppalúði is lazy, so he typically stays home. But Grýla is hideous, inhumanly strong, lustful, and cannibalistic. She is originally mentioned in the Prose Edda in a rhymed verse attached to Snorri Sturluson’s Skáldskaparmál and appears in the Sturlunga Saga. The giantess has an insatiable appetite for human flesh. She can detect misbehaving children year-round, but only comes from the mountains during the winter to searach towns and villages for a meal. Any children she finds are carried home in a skin sack. Her favorite meal is stew of naughty kid.

The Yule Lads and their black cat resided in a remote cottage near a cave in the mountains and are clad in wool cloth, sheepskins, and felt. Their original role was to strike fear in the hearts of children. They come to town one-by-one during the 13 nights before Yule. After Yule, they depart one-by-one in the order they arrived, thus each lad is able to harass the population and cause all sorts of mischief for 13 days.

Below is the poem The Yuletide Lads by Jóhannes úr Kötlum, first published in his 1932 book Jólin koma. (English translation by Hallberg Hallmundsson.)

The first of them was Sheep-Cote Clod.

He came stiff as wood,

to prey upon the farmer’s sheep

as far as he could.

He wished to suck the ewes,

but it was no accident

he couldn’t; he had stiff knees,

not to convenient.

The second was Gully Gawk,

gray his head and mane.

He snuck into the cow barn

from his craggy ravine.

Hiding in the stalls,

he would steal the milk, while

the milkmaid gave the cowherd

a meaningful smile.

Stubby was the third called,

a stunted little man,

who watched for every chance

to whisk off a pan.

And scurrying away with it,

he scraped off the bits

that stuck to the bottom

and brims – his favorites.

The fourth was Spoon Licker;

like spindle he was thin.

He felt himself in clover

when the cook wasn’t in.

Then stepping up, he grappled

the stirring spoon with glee,

holding it with both hands

for it was slippery.

Pot Scraper, the fifth one,

was a funny sort of chap.

When kids were given scrapings,

he’d come to the door and tap.

And they would rush to see

if there really was a guest.

Then he hurried to the pot

and had a scrapingfest.

Bowl Licker, the sixth one,

was shockingly ill bred.

From underneath the bedsteads

he stuck his ugly head.

And when the bowls were left

to be licked by dog or cat,

he snatched them for himself,

he was sure good at that!

The seventh was Door Slammer,

a sorry, vulgar chap:

When people in the twilight

would take a little nap,

He was happy as a lark

with the havoc he could wreak,

slamming doors and hearing

the hinges on them squeak.

Skyr Gobbler, the eighth,

was an awful stupid bloke.

He lambasted the skyr tub

till the lid on it broke.

Then he stood there gobbling,

his greed was well known,

until, about to burst,

he would bleat, howl and groan.

The ninth was Sausage Swiper,

a shifty pilferer.

He climbed up to the rafters

and raided food from there.

Sitting on a crossbeam

in soot and in smoke,

he fed himself on sausage

fit for gentlefolk.

The tenth was Window Peeper,

a weird little twit,

who stepped up to the window

and stole a peek through it.

And whatever was inside

to which his eye was drawn,

he most likely attempted

to take later on.

Eleventh was Door Sniffer,

a doltish lad and gross.

He never got a cold, yet had

a huge, sensitive nose.

He caught the scent of lace bread

while leagues away still

and ran toward it weightless

as wind over dale and hill.

Meat Hook, the twelfth one,

his talent would display

as soon as he arrived

on Saint Thorlak’s Day.

He snagged himself a morsel

of meet of any sort,

although his hook at times was

a tiny bit short.

The thirteenth was Candle Beggar

‘twas cold, I believe,

if he was not the last

of the lot on Christmas Eve.

He trailed after the little ones

who, like happy sprites,

ran about the farm with

their fine tallow lights.

Early on, the Yule Lads attributes ranged from mere prankster to homicidal child-eating monster. That changed in 1746, when the King of Denmark made a public decree prohibiting parents from frightening children with monsters and fiends like the Yule Lads. Since then, the Yule Lads have ceased threatening children’s lives and become benign. Though, they continue to be thieving scoundrels who punish naughty children by putting rotten vegetables into their socks.

Families can revive this tradition by dispensing with “Elf on a Shelf” and purchasing a set of Yule Lads. In the 13 days leading up to Yule, place the appropriate day’s lad somewhere in the house. Continue until all 13 lads adorn your shelves, tables, and mantels.

Yule Goat

The Yule Goat is a Northern European tradition whose origins date back to ancient Pagan festivals. The last sheaf of grain from the harvest was believed to possess magical properties and was saved for the Yule celebrations. It was crafted into the shape of a goat and called Julbocken, though roughly hewn wood was sometimes used as well. A similar tradition exists in ancient Slavic beliefs. In the Slavic Koliada festival, Devac the god of the fertile sun and the harvest is honored. Devac (also known as Dazbog or Dažbog) is represented by a white goat who demands offerings in the form of presents.

The Yule Goat is a Northern European tradition whose origins date back to ancient Pagan festivals. The last sheaf of grain from the harvest was believed to possess magical properties and was saved for the Yule celebrations. It was crafted into the shape of a goat and called Julbocken, though roughly hewn wood was sometimes used as well. A similar tradition exists in ancient Slavic beliefs. In the Slavic Koliada festival, Devac the god of the fertile sun and the harvest is honored. Devac (also known as Dazbog or Dažbog) is represented by a white goat who demands offerings in the form of presents.

The Norse gods Njord and Thor also have connections to goats. A kid goat was often sacrificed in honor of the Norse god Njord and to ensure a bountiful harvest and Thor rides through the sky in a chariot drawn by two goats, Tanngrisnir and Tanngnjóstr.

Julebukking is a Scandinavian tradition similar to the English tradition of wassailing. Julebukkers dress in costume and go door-to-door, singing festive songs, preforming short plays, or engaging in pranks. One of the characters is the Yule Goat, who generally makes a nuisance of himself and demands gifts. The Julebukkers are rewarded with hot beverages and baked goods while the household tries to guess who’s in the goat costume. In some traditions, a person from each household visited is expected join the band of Julebukkers and continue through the neighborhood.

Another popular Yuletide prank is to place a large Yule Goat in the yard of a friend or neighbor without the household noticing. The household successfully pranked has to get rid of the goat the same manner, thus the Yule goat spreads good cheer as it makes the rounds of the neighborhood.

Today, it’s possible to find Yule Goat ornaments. The figures are typically made of straw and bound with red ribbons. Large versions of the Yule Goat are frequently erected in Scandinavian towns and villages around Christmas time.

Add the Yule Goat to your holiday traditions by going Julebukking or pranking your neighbors with a Yule goat.

Additional Reading

Arnarsdóttir, Eygló Svala. “Forgotten Yule Lads and Lasses”. Iceland Review. 22 December 2010.

Faulkes, Anthony. (Trans.) Edda. Everyman’s Library, Random House, 1995.

“Hallberg Hallmundson’s translation of ‘Jólasveinarnir’ by Jóhannes úr Kötlum”. Jóhannes úr Kötlum, skáld þjóðarinnar.

Kropej, Monika. Supernatural Beings from Slovenian Myth and Folktales, Scientific Research Centre of the Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts, 2012.

Hollander, M. Lee (Trans.) Heimskringla: History of the Kings of Norway. University of Texas Press., 2007.

Orchard, Andy. Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell National Library, 1997.

Sermon, Richard. “The Celtic Calendar and the English Year.” Mankind Quarterly: Summer 2000: Volume XL, Number 4.

Schager, Karin. Yule goat in Folklore and Christmas Tradition. Rabén & Sjögren, 1989.

Simek, Rudolf. (Trans. by Angela Hall) Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewster Company, 2007.

Wonderful writing and the research you put into this article is amazing.

Thanks! I had a lot of fun writing this one.