My favorite stories have strong sense of place. I absolutely love when an author pulls you into the story so deeply that you’re startled to find there isn’t six feet of snow outside when you put the book down. This is achieved though worldbuilding.

Most people think worldbuilding is easy. Science fiction and fantasy writers get told it’s easy because they can just make stuff up. Historical fiction writers get told it’s easy because they can just look stuff up. Writers who use contemporary settings are told it’s easy because it’s just the real world, duh. Savvy writers know worldbuilding is anything but easy.

Readers who find mistakes relish leaving bad reviews. To avoid these mishaps, successful writers create custom-made reference material for their stories. This is often referred to as a story bible.

If you have an aversion to using the word bible, simply refer to your reference material as your novel handbook or story key. Feeling adventurous? Consider calling your reference material the novel’s atlas, compendium, conspectus, enchiridion, treaties, or vade mecum!

A story atlas contains all the information an author needs to track while writing. This includes character description and bios, descriptions of animals or pets, notes about important items, timelines and calendars, story arcs, and plot points.

Examples from my story atlas:

- The name of the blacksmith’s horse is Anvil—he’s sturdy enough to take a beating and just as black. (Friesian, gelding.)

- The wizard has an amber adder stone used for divination. The hazel rune is carved into the side you look though.

- The main character is pregnant. Fetal development and pregnancy milestones are tracked on a calendar along with everything else happening in the story.

Other items to add to your story atlas include:

CREATURES, CULTURE, & SOCIETIES

This includes races, religions, power structures (including the role of privilege, prejudice, and suppression), governmental organization, arts and entertainment, traditions, and trade. Also consider how the cultures and societies relate to one another. Who are their allies, enemies, and trade partners?

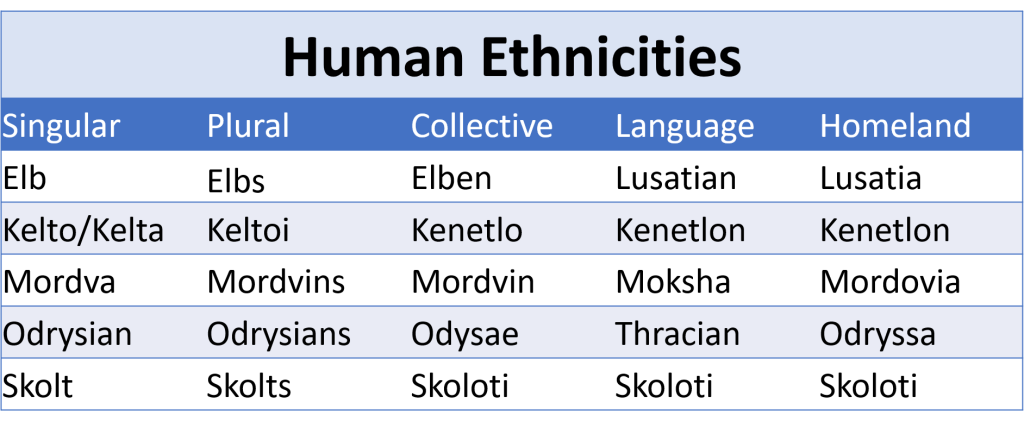

For my book I created a spreadsheet for this information. It not only keeps the information organized but having it at my fingertips also ensures spellings are consistent.

ATLAS SAMPLE

CUSTOMS & HISTORY

Every story has a backstory. What power shifts occurred before the opening of the novel? Where there any traumatic or catastrophic events? What legends arose from that history?

In The Council of the Animals by Nick McDonell, the dogs refer to the bacon wars (military dogs were rewarded for their service with bacon) and the great calamity (a pandemic that decimated the human population.) Both events help shape the narrative as well as highlights why the dogs view of humanity was vastly different from the ape’s perception of humans.

Another item to consider is time. How is time measured? Does the society use a solar or lunar calendar? How do they reckon years?

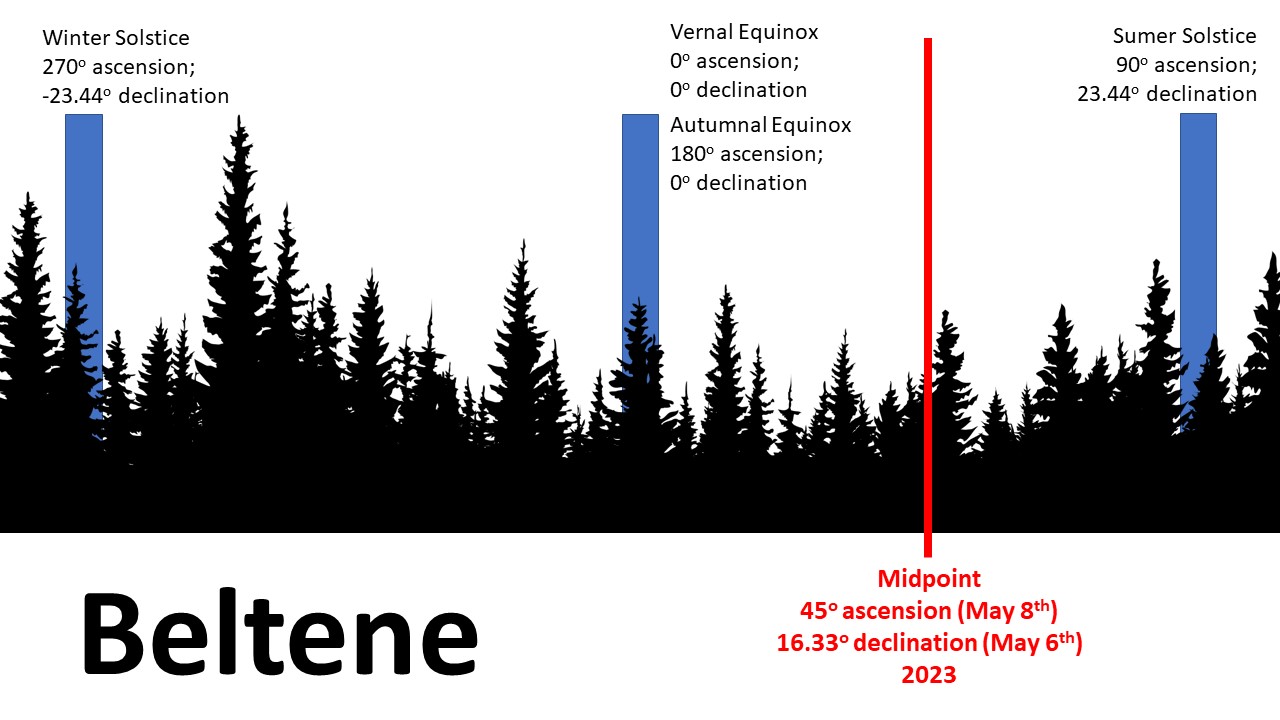

Inability to accurately measure time left me struggling for answers with my own novel. Since my main character is pregnant and has a literal and figurative eye on the horizon, I needed to be able to calculate the location of the sun on the horizon. Finding the endpoints (solstices) and the midpoint (equinoxes) was easy, but between those points things got muddled. And yes, all my sketches and notes went straight into my story atlas.

ATLAS SAMPLE

GEOGRAPHY & MAPS

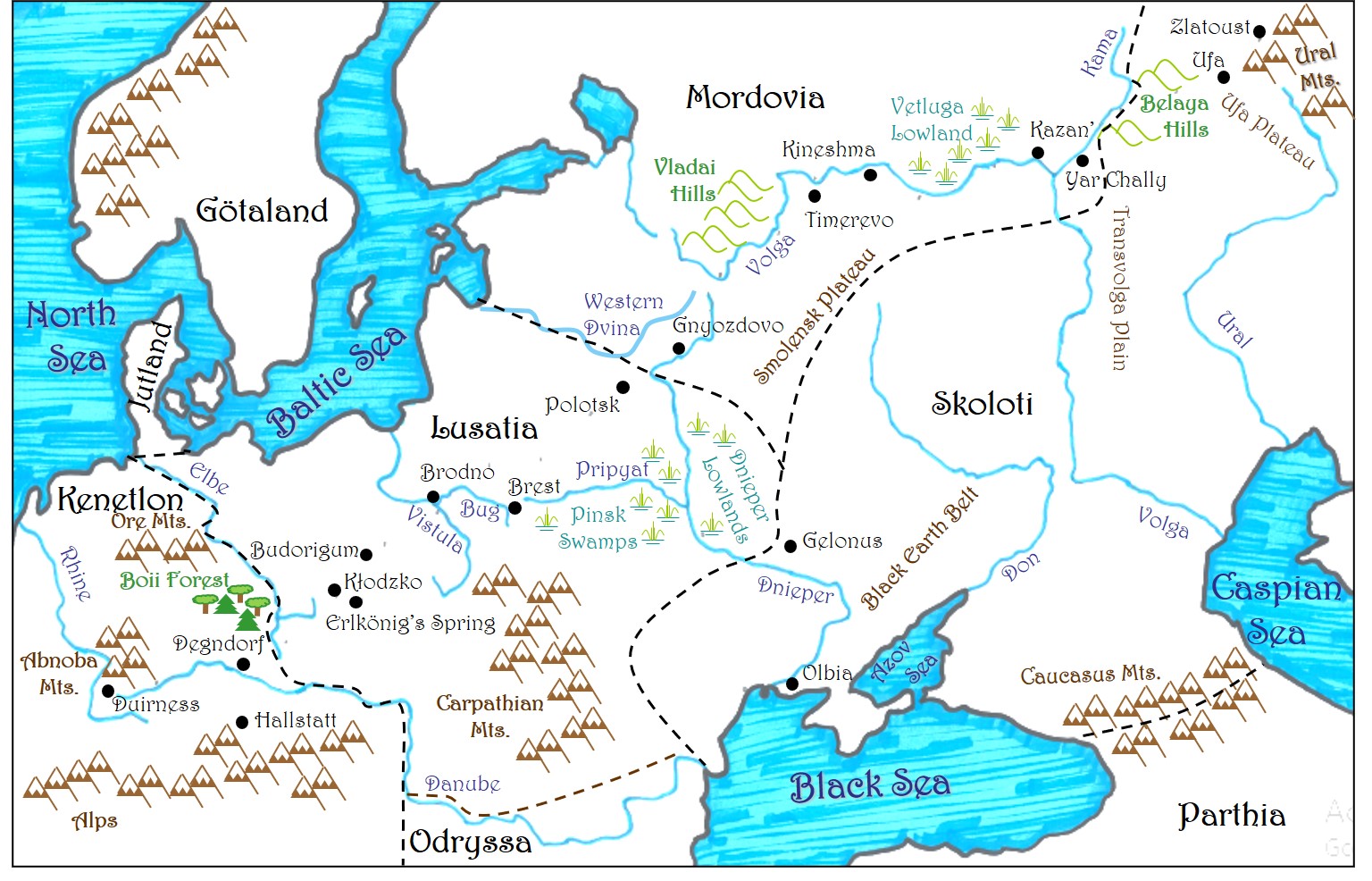

Consider where settlements are located and how the physical geography shapes the borders and landscapes. What natural or manmade features influence the story? Create descriptions for all locations including climate, seasons, and basic ecology. Pay particular attention to how each will impact the story.

In Game of Thrones, by George R. R. Martin, winter means White Walkers can move south, but the Night’s Watch and wall is supposed to protect the people of Westeros. Thus, weather and geography play an outsized roll in the story and add a significant measure of depth to the worldbuilding.

If you have the time and talent, creating a map of your world will help keep place names and geography from becoming muddled. Also, readers love maps. If you’ve created a map for your story atlas, it’ll be easy to find a cartographer to turn that into a real map for your book when the time comes.

ATLAS SAMPLE

MAGIC SYSTEMS & TECHNOLOGY

Who has the ability to wield magic or control technology? Whatever system you create has to remain consistent throughout the novel. And when there are exceptions, those need explained.

For example, in J.K. Rowling’s Harry Potter series, magic is hereditary, passed down through a few magical families, yet Hermione Granger is muggle-born. This explained by claiming there’s a Squib somewhere in Granger’s family tree.

Also, maintaining the balance between science and fiction is difficult. If the science in science fiction isn’t plausible, the author risks losing the reader. Ashes by Ilsa Bick manages this balance beautifully. A massive electromagnet pulse disabled all electronics (and killed anyone with a pacemaker) but did not damage solid state technology, like the park ranger’s 1970s vintage truck.

LANGUAGE

In Watership Down, Richard Adams sprinkles Lapine words throughout the text and uses them repeatedly, so the readers lean them gradually. By the end of the book, one rabbit insults another with the phrase “Silflay hraka, u embleer rah!” (“Grazing turd, you stinking chief!”) Not only does the phrase make sense, but though repeated use of the words, the readers fully understand without ever having seen that exact phrase before.

You don’t need to go crazy like Tolkien or Richard Adams and create your own language, like Elvish or Lapine. However, it’s important to recognize that different cultures have different languages. This should cause problems for your characters and will cause more problems for readers if language barriers are not handled well.

Slang is good. Regardless of whether you’re writing high fantasy or historical fiction, this helps ground the reader. In the Outlander by Diana Gabaldon, Claire uses the expletive, “Merd,” or if things are really bad, “Merd on toast!” Gabaldon also employs a smattering of other French and Gaelic words in individual characters’ patterns of speech, which adds richness and complexity to the characters.

If you use foreign words (or invent your own), create a glossary and make sure to use them consistently.

If you aren’t ready to tackle differences in dialect, either all the characters must be multilingual, which is improbable, or they need a translator. This can be a person, a computer, or the equivalent of the infamous Bable Fish, which appears in the Hitchhikers Guide to the Galaxy by Douglas Adams. Alternatively, characters can just walk around confused, having no idea what anyone is saying, which is a technique I employed in a couple chapters of my own book.

Closing Thoughts

Don’t lose sight of the story amidst the chaos of worldbuilding. Bigger isn’t always better. Too much detail will bog down the story and frustrate readers.

If you feel overwhelmed by the world-building process, take a step back. Only focus on things that directly impact your characters. Worldbuilding is not a one-time event, nor should it be fully completed before writing begins. Worldbuilding is a process. Leave room for your character to surprise you and give yourself permission to let your story atlas grow with each new chapter.

For more information on worldbuilding see:

The Story Bible: What It Is and Why You Need One | Jane Friedman