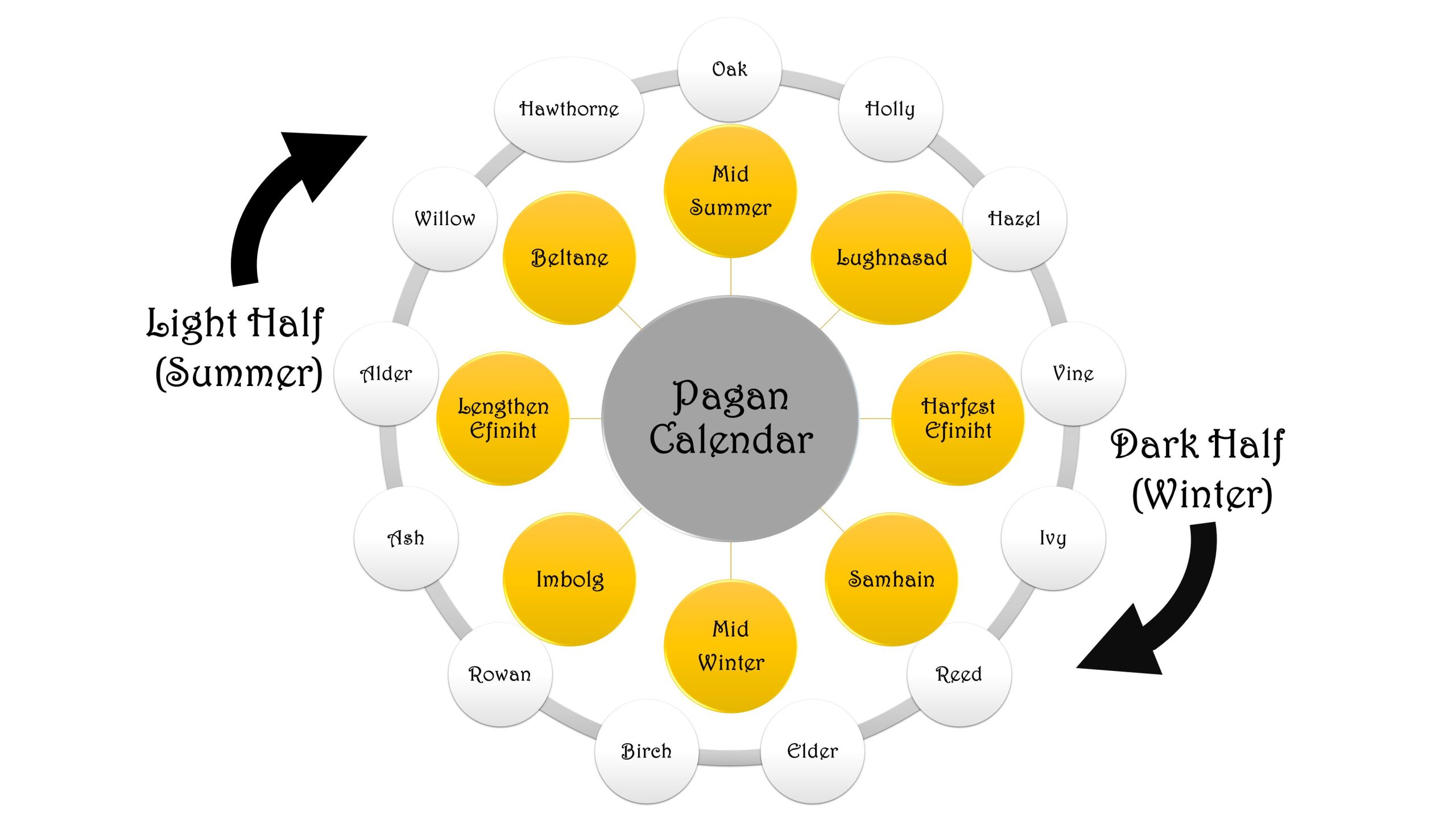

For many pagans, the New Year starts at Samhain. This framework merges solar and lunar cycles, dividing into just two seasons, summer and winter. The thirteen months take their names from thirteen of the sacred trees listed in the ogham. Holy days derive from the solar cycle, with the principal Celtic festivals occurring at the mid-points between the solstices and equinoxes. These days are considered auspicious as being part of the time between times.

This modern pagan calendar conflates the holy days from both the Celtic and Germanic traditions with the additions of Midsummer and Yule representing the solstices. The Lengthen Efiniht and Harfest Efiniht are the vernal and autumnal equinoxes, respectively. Although, many pagans refer to the vernal equinox as Ostara and the autumnal equinox as Mabon.

Some of the holy days already have undeniable associations. The most obvious being Lugh/Lughnasad and Belenus/Beltene. Owing to the blending of Celtic and Germanic traditions, the remaining holy days are not so easily assigned. For those of us who prefer venerating Celtic deities, that means that one cannot simply point to archeological evidence and come up with a definitive answer, because no such answer exists for half the sabbats.

After a fair bit of research, reading, and soul searching, I have matched each sabbat with a Celtic deity. These are presented below:

Samhain—Daghda

Samhain’s association with death is undeniable. The festival marks the death of the old year and the beginning of the Celtic New Year. Slaughtering cattle, ritual mourning, and the triple killing of the sacral king are the day’s primary activities.

Daghda’s association with death comes in the form of lorg anfaid, the club of wrath, which kills with one end and restores life from the handle, making him a suitable symbol to embody death and rebirth. His two pigs, one of which was always growing while the other is always roasting, cements his association with slaughter. The ancestral god of death, Donn, is sometimes referred to as Daghda Donn, thus this god may have originated from the death aspect of Daghda. In exchange for a battle plan, Daghda mates with Morrigan (the raven-goddess of war and fertility) at Samhain, thereby linking him to the festival. Tales depict Daghda as being immensely wise in his roles as the all-father, druid, and king.

Despite his great power and prestige, Daghda is often portrayed as uncouth, oafish, comical, and even crude. Physically, he is a large bearded man who wears a short rough tunic that barely covers his backside, over which he sometimes wears a hooded cloak. Daghda’s other possessions include: coire ansic, the cauldron of plenty, which never runs empty and from which no man ever leaves unsatisfied; uaithne, a magical oak harp which can control men’s emotions, direct battles, and change the seasons; and ever-laden fruit trees.

Daghda’s name means “the good god” or “the great god.” The name originates from the Proto-Celtic words *dago- (good) and *da- (give), thus he is the good giver. This fits well with his mythical associations of the cauldron of plenty as well as his ability to give life.

I imaging him at sunset stirring his bubbling cauldron over a roaring fire, while ravens bear witness to the proceedings. I like to think of him as everyone’s oafish uncle, uncouth and ugly.

Eponalia – Epona

Of all my choices, this one surprises me the most. Before researching festivals surrounding the winter solstice, I had no idea there was an actual Celtic holyday in December.

Epona means ‘Great Mare,’ fitting for a goddess of horses and protector of cavalry, whose cult spread across the entire continent of Europe. The name derives from the Proto-Celtic word *ekʷos (horse). Normally, I think of Epona in May or June, with a fresh crop of new foals grazing in lush pastures, but the goddess is a complex one.

In one account of Epona’s origin story, her mother is a mare while her father is human. This may relate to an Irish ritual in which the King’s sovereignty is granted by mating with a white mare that is the embodiment of a goddess. The aversion to eating horse meat may also derive from Epona’s veneration.

As a goddess of fertility, she is often depicted with a cornucopia, coins, and disproportionally large ears of corn and grain. She is always accompanied by horses and often with foals. But it is her funerary symbolism that is most pressing at the time of the winter solstice. She and her horses lead souls to the afterlife. In several depictions, Epona carries a large key that unlocks the gates to the otherworld, fitting since Celtic cart burials seem to indicate that horses are necessary to make the final journey.

The Romans held the festival of Eponalia in Epona’s honor on December 18th. In Wales, the folk ritual of Mari Lwyd (Grey Mare) also occurs in December, which folklorists believe is an apparent survival of the veneration of the goddess. Early Christian writers noted that the celebration occurred “near Christmas,” though the date varied and it was often indistinguishable from wassailing, save that the revelers carried horse skulls. Similar festivals occurred across Ireland, Scotland, and Britain, but those had largely died out by the 1700s.

The festival began at dusk and continued late into the night. Folklorist Ellen Ettlinger believed that Mari Lwyd represented a death horse, whereas Christina Hole suggested the mare was a bringer of fertility. Both are aspects of Epona.

Mari Lwyd, Lwyd Mari

A sacred thing through the night they carry.

Betrayed are the living, betrayed the dead

All are confused by a horse’s head.

— Vernon Watkins, “Ballad of the Mari Lwyd”, lines 398–400

I like to imagine Epona and her mares in a bleak moonlit winter landscape.

Imbolg – Brigid

As Daghda’s daughter, Brigid’s birth and upbringing were seeped in mystery and magic. Like her father, she supplied limitless food from her larder, whose contents never diminish. As a mother herself, she fulfills the role of a mother goddess with a heavy fertility aspect. Having been raised by druids, she in the protector of druidic knowledge and wisdom.

Brigid is the patroness of poetry, scared springs, and the arrival of spring. Among her many skills was smithcraft, which may account for the prevalence of associations with sacred flames. At her sacred well in Kildare, a hedge surrounded the flame, through which it is said no man can pass without going insane or being severely crippled. In her healer role, she is the protector of women in childbirth. For companions, Brigid has two oxen, Fen and Men; Torc Triath, the King of the Boars; and Crib, the King of Sheep, cementing her place as the guardian of livestock and domestic animals.

Brigid means ‘exalted one’ and derives from the Proto-Celtic *Brigantīno (chief), thus the goddess may have been a chieftain in her own right. She is linked to the British deity Brigantia. The two goddesses may, in fact, be one and the same.

The festival of Imbolg is dedicated to the Goddess, though the etymology of the word is unclear. The most common explanation is that it derives from the Old Irish i molec (pregnancy of ewes), though the 10th century Cormac’s Glossary derives if from oimelc (ewe milk).

I am inclined to accept Cormac’s etymology. In early cultures, milking was exclusively women’s work and Brigid’s cows supposedly produced a lake of milk. In the depth of winter, when game is scarce and stores are running low, milk provided a welcome addition to the diet. Sheep are the first of the domestic animals to begin lactating, thus her festival marks the onset of lambing season.

I imagine Brigid with a child on her hip, checking her ewes and lambs by lantern light, with a churn somewhere in the vicinity.

Lengthen Efniht – Abnoba

Abnoba is my favorite Goddess, perhaps because so little is known about her. The Gaulish goddess was worshiped in the area now known as the Black Forest and even has a mountain range named after her. Stretching from the Rhine to the headwaters of the Neckar, the Abnoba Mountains encompass the Odenwald, Spessart, and the Baar foothills of the Swabian Alps. According to Tacitus’s Germania, the source of the Danube River was a grassy slope named Mount Abnoba. It is no wonder then, that she is interpreted as a forest and river goddess.

As Mistress of the Forest, it seemed logical to place her opposite Karnunnos in the calendar. The divine huntress is armed with a bow and quiver. Celtic hunter deities had close relationships with their prey, often being protected by the very beasts they hunted. Likewise, the goddess protects both the hunters and their prey, maintaining balance in the forest. In depictions of Gaulish hunter goddesses, the women wear lunar amulets. The moon has long been associated with women owing to their monthly cycles, lending a fertility and maternal aspect to her cult.

The etymology of the name Abnoba is ambiguous. It may be a combination of the Proto-Celtic words *abon- (river) and *bā (die), which could be a reference to the Danube Sinkhole, where the sacred river loses much of its water to the Rhine. Documented cases of the Danube completely disappearing date to 1874. If such an event occurred at any point in antiquity, possibly during a severe drought, the people of the time no doubt saw it as an ill omen in need of an explanation. What better explanation is there than a river goddess?

The mighty Danube now goes completely dry at the sinkholes approximately 155 days per year, the result of global warming and heavy water use in recent years.

Another possible meaning for her name derives from combining either of the Proto-Celtic words *albiyo- (world) or *albeies (alps) with *noybo- (holy). Thus making her the goddess of the holy mountains, very likely the same mountain that bears her name.

Since hares begin their frantic dances in the spring, I envision Abnoba in the forest with her bow and quiver, accompanied by both hare and doe.

Beltene – Belenus

Generally regarded as ‘The Shining God’ owing to his association with the sun, Belenus is thought to derive from the Proto-Celtic *bāno- (white, shining). As a solar deity, he is associated with horses. In Cornwall and Somerset, the tradition of riding hobbyhorses during May Day celebrations might be a holdover from pagan festivals honoring the God.

However, looking solely at the root, *belyo- (tree) is a better fit. I see this as a possibility given the prevalence of May Bush traditions scattered across Europe. The tradition involves bringing a small tree into the home and decorating it with flowers, ribbons, candles or rushlights, and other decorative items. However, in some instances it was decorated where it stood, only to be cut later. Throwing the tree into a ceremonial bonfire marked the end of the festivities. Scottish anthropologist James Frazer claims such customs are relics of tree worship.

When transitioning from Proto-Celtic to Goidelic *belyo- becomes bile (large tree/tree trunk) and the Proto-Celtic *tefnet- (fire) becomes tene in Goidelic, thus you have biltene, essentially, a bonfire. Bonfires are an integral part of Beltene celebrations, which mark the beginning of the pastoral season. As part of the festivities, cattle were driven between a pair of bonfires in order to garner Belenus’s blessing before being driven to their summer pasture. The flames, smoke, and ash were believed to have restorative powers that protected man, beast, and crops from disease. Prior to kindling the sacred fires, all flames in the village were extinguished. Hearth fires were relit using torches from the communal flame.

John Ramsay describes Scottish Highlanders kindling sacred fires at Beltene. Ronald Hutton claims the holy flames were kindled by the most primitive means possible, friction between wood. Frazer viewed the fires as possessing imitative or sympathetic magic, which bodes well for the association with the sun. Thus, Belenus’s may owe his status as a solar deity to simply being the lucky bastard who discovered how to kindle a flame.

The god is also associated with healing, as well as sacred and curative springs. Votive offerings of both oak and stone have been recovered from sacred springs and wells, many of which depict swaddling infants and body parts requiring a cure. Many herbs used by the druids bear his name, notable among them several members of the Solanacea family that have medicinal properties when properly prepared and used in small quantities. The connection to medicinal herbs bears credence to the healing aspect of the god. Visiting healing springs remains an important aspect of Beltene today.

Midsummer – Taranis

The Celts venerated all natural phenomena, but thunder especially so. Any place where lightening struck was considered sacred thereafter, so it’s not surprising they had a Thunder God. Many representations of the bearded god depict him with a thunderbolt in one hand and a wheel in the other. As a sky-god, Taranis has power over all the elements: sun, rain, and storms.

The wheel is an important symbol in Celtic religion and society. Wheel pendants and amulets have been worn since the Bronze Age and votive offerings of wheels have been recovered from shrines, rivers, and burial mounds. Numerous Celtic coins also depict wheels. The wheel symbolizes the sun as it traverses the sky and is where the concept of ‘the wheel of the year’ originates.

Taranis’s name derives from the Proto-Celtic *torano- (thunder). In some inscriptions, he is merely the God of the natural phenomena thunder; in others, he is ‘The Thunderer,’ indicating that his personality was just as blustery as the weather. While there is no recorded festival associated with Taranis, placing him at Midsummer seems appropriate. There can be no better time to honor the god than during a summer storm with lightening crackling across the sky.

Lughnasad – Lugh

Julius Caesar described a god known as “the inventor of all the arts” as being the most revered deity in Gaul. That deity is Lugh. He is credited as being a wright, smith, swordsman, harpist, poet, historian, and sorcerer. As a Warrior-King Lugh defeated the Fomorians in battle, but spared the life of Bres, the former king, on the condition that Bres teach him how and when to plough, sow, and reap, thereby adding farming to his skill set. Lugh is also credit with inventing horseracing and fidchell (a Gaelic game similar to chess.)

Often described as a youthful spear-wielding horseman, Lugh wears a green mantle, silver broach, and bears a black shield. Lugh’s fiery spear, sleg, is made of yew. It is this unstoppable, magical spear that earns him the epitaph, Lugh the Long Arm. For companions he has his mount, Aenbharr, who travel over land and water and a greyhound, Failinis, both of which were gifts from his foster-father, the sea god Manannán. Among Manannán’s other gifts were Fragarach, his sword, and Lugh’s boat, Sguaba Tuinne, the Wave-Sweeper.

Lugh’s name derives from the Proto-Celtic *lugiyo- (oath), making him the god of oaths, truth, law, sworn contracts, and rightful kingship. Consequently, his name is often evoked for overseeing journeys and business transactions.

Seen as a celebration of Lugh’s mastery over agriculture, the harvest festival that bears his name was actually founded as a funeral feast in memory of his foster mother. The month-long festival included: religious ceremonies; feasting; music and storytelling; trading food, livestock, and other wares; proclaiming laws, settling legal disputes and drawing up contracts; and marriages. The festival closed with the Tailteann Games, an event similar to the Olympics. The modern concept of fairs is believed to be survivals Lughnasad celebrations.

The festival involved the ceremonial first cutting of grain, which was carried to a hilltop where it was presented as an offering to Lugh and buried. Berry picking and partaking of these ‘first fruits’ are popular ways to celebrate and honor the god. Since these actives took place on hilltops, hiking and berry picking remain an important way to celebrate Lughnasad today. In modern Irish, Scottish Gaelic, and Manx, the month of August is still known by its association to Lugh, Lúnasa, Lùnastal, and Luanistyn, respectively.

Bhuiridh—Karnunnos

There is no denying Karnunnos’s association with the autumnal equinox. Of all the hunted beasts, the stag was the most prominent. The Proto-Celtic word for autumn is *sido-bremo, translated as bellowing of the stags. This survives in Gaelic as Bhuiridh, the day of roaring, which is officially set as September 20th. In Proto-Celtic *karno- means horn, thus Karnunnos is the horned god. As a shape-shifter and Lord of the Hunt, it is fitting that he be associated with the beginning of the rut.

The surviving Karnunnos iconography indicates that the Celts only began to view their gods in human form after the Roman Conquest of Gaul. Karnunnos was never equated with any of the Roman gods in the same manner that countless others were, perhaps because he was to unique to be easily translated onto the Roman pantheon.

Often depicted with antlers, seated cross-legged as is typically associated with traditional shamans, Karnunnos is generally surrounded by animals. Stags and ram-horned snakes are the most common, but bulls, dogs, and rats appear in conjunction with the god on occasion. He is usually holding or wearing a torc, indicating that he either held power himself or had the authority to bestow it. The god was also associated with material wealth. This is evidenced by the frequent depictions of coin purses that often accompany his image, and in one instance a stag vomiting coins is thought to symbolize the fecundity of the forest.

The Celtic battle horn, the carnyx also bears the root word ‘horn’ and may give an indication of the god’s role in Celtic society. As long as the trumpeters themselves, the carnyx rose well above the heads of the crowd. Designed to evoke fear in the hearts of their enemies, the bells were cast to resemble open-mouthed serpents or other beasts whose ghastly calls befitted the dissonant sounds the horn produced. Thus, the coins may be the result of loot or booty taken from enemies or neighboring tribes since raids have long been glorified in Celtic mythology. Coin hordes were often buried, so it is fitting that Karnunnos attested to ruling over the hidden treasure of the underworld, a world commonly linked to serpents.

I imagine Karnunnos mid-transformation, bearing hooves and antlers, adorned with his is golden torc, standing at the forest’s edge, surrounded by the bounty of the harvest.

Closing Thoughts

As we move into the dark half of the year, take time to mourn all those who have died in the previous year. Now is a time for introspection, slow down and meditate on the gods. Thank them for the bounty of the prior year and make plans for the year to come.