As early as the neolithic era, humans sought ways to mark the passage of time and predict celestial events. Their methods, no matter how carefully thought-out, were often thwarted by the very solar and lunar cycles they wished to track. When seasonal drift occurred and the months no longer aligned with the weather, people simply adjusted the calendar or adopted an entirely new one.

As early as the neolithic era, humans sought ways to mark the passage of time and predict celestial events. Their methods, no matter how carefully thought-out, were often thwarted by the very solar and lunar cycles they wished to track. When seasonal drift occurred and the months no longer aligned with the weather, people simply adjusted the calendar or adopted an entirely new one.

Seasonal Drift: a gradual misalignment of seasons and calendar dates, owing to the calendar not accurately capturing the length of the solar year.

An example of this occurred in 1582. Pope Gregory XIII instituted the new Gregorian calendar to correct an error in the Julian calendar that was causing Easter celebration to occur at the wrong time. As a result, 10 days were skipped so that Thursday, October 4th was followed by Friday, October 15th.

The world is filled with calendars: Chinese calendar, Hebrew calendar, Iranian calendar, and Buddhist calendar, to name a few. There’s an even longer list obsolete calendars, some of which include, Attic calendar, Old Icelandic calendar, and the Coligny calendar. When calendars no longer serve their purpose, they are abandoned. In its place, something new is adopted. The modern pagan movement is not immune to this pressure.

The Tree Calendar

As much as I love trees and the ogham, there isn’t any archeological evidence that the three calendar, now accepted as canon by many pagans, was ever used. This is not to say that it isn’t a useful tool or that it doesn’t have its place. I’ve used the calendar as a framework for creating personal holydays and employed it in my novel, Klara’s Journey. However, I recognize that like my book, the tree calendar is a work of fiction.

See more about the tree calendar here: The Wheel of the Year

So, if not from ancient pagan cultures, what are the tree calendar’s origins?

In 1948, Robert Graves published The White Goddess. In the book, he claimed the order of Ogham formed a 13-month calendar, where each tree represented 28-day lunar cycle. Graves’s value as a poet aside, there are serious flaws in his scholarship which has led archaeologists, historians, and folklorists to out-right reject the work.

Graves’s calendar approaches time keeping from a decidedly creative perspective and bears no relation to any actual historical calendars. Among the problems with Graves’s calendar is that the ogham originally contained 20 characters. An additional 5 characters were added later, for a total of 25. Neither lends itself to a 13-month calendar. Further, the ogham was invented in the 4th century. At that time both, the Coligny (Celtic) and Jullian (Roman) calendars were widely used in Celtic regions. Finally, one lunation simply isn’t 28 days, nor are their 13 lunar cycles in a year.

Lunation: one lunar month. The period of time between successive new moons.

One lunation is 29.53 days, resulting in 12.36 lunar cycles per solar year. This was a fact early civilizations knew well. Whether calendars were Celtic, Germanic, or Grecian they contained 12 months that alternated between 29 and 30 days. To account for the additional solar time and prevent seasonal drift, intercalary months were added at specific intervals. Because these early calendars tracked both the sun and the moon, they were called lunisolar.

Intercalary: a month inserted in the calendar to harmonize it with the solar year.

Lunisolar: a calendar year divided according to the phases of the moon but adjusted to fit the length of the solar cycle.

Coligny Calendar

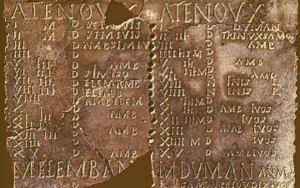

One such lunisolar calendar attributed to the Celts is the Coligny calendar, whose name derives from the fact that it was found in Coligny, France in 1897.

The calendar is a bronze plaque of Gaulish origin that is preserved in 73 fragments. It dates to the 2nd century and measures 4’ 10” wide by 2’ 11” tall. It lays out a five-year cycle of 62 months, where each year contains twelve lunar months. The lunar phase is tracked with exceptional precision, adjusted with an intercalary month every 2.5 years so the cycle also aligns with the solar year.

Since calendars tend to be more conservative than rituals, rites, and cults, the astronomical format of the calendar likely predates the 2nd century. While its inception is unknown, the similarities to Insular Celtic and Continental Celtic calendars suggest its usage might have been adopted as early as Hallstatt C, roughly 800 BCE.

The Coligny calendar lists the days, weeks, months, seasons, quarter days, and festivals. Each month was divided into two fortnights, the first (bright fortnight) lasted 15 days and the second (dark fortnight) lasted 14 or 15 days depending on the number of days in the month. Olmsted further speculates that each fortnight was divided into 5-day weeks, so that each month was composed of 6 weeks.

Owing to the accurate tracking of the lunar cycles, each month always started at exactly the same lunar phase. Which, according to Pliny the Elder, was the 1st quarter moon.

“This is done more particularly on the sixth day of the moon, the day which is the beginning of their months and years, as also of their ages, which, with them, are but thirty years. This day they select because the moon, though not yet in the middle of her course, has already considerable power and influence; and they call her by a name which signifies, in their language, the all-healing.” — Pliny, Natural History 16.95

This may seem like an odd time to begin a month, but when you consider that the Celts were obsessed with “between times” and held their major festivals at the midpoints between the solstices and equinoxes, it makes a quiet sort of sense. Starting each month on the 1st quarter moon also has the benefit of being very easy for layfolk to confirm by direct lunar observation.

Another major difference between the Coligny calendar and the Gregorian calendar is that each new day begins at sundown rather than midnight. This tradition was recorded by Julius Caesar in the Gallic Wars, “[the Gaulish Celts] keep birthdays and the beginnings of months and years in such an order that the day follows the night.” Observing holydays the evening before the festival date is still a common holiday practice, as seen in the folkloric traditions of Halloween (Hallows Eve), Christmas Eve, New Year’s Eve, etc.

A sample month created using Olmsted’s interpretation of the Coligny calendar is presented below. The fortnights are color coded with yellow representing the “light” fortnight and black representing the “dark” fortnight. The full moon always falls in the light fortnight and the new moon always falls in the dark fortnight. Because “days” were reckoned by nights, the light/dark notation is likely just a reference to how much moonlight was available.

The upcoming month is Cutios, which is translated as the month of invocations. The 1st quarter moon falls on October 21st, so that is the first day of the month. Recall, that the first “day” of the month begins at sunset on October 21st, not at midnight. To help with tracking the days, I have added the Gregorian dates below the lunar phases.

It is also important to note that Samhain falls on November 9th. In the Coligny calendar, festival days were recorded as “movable feasts” and occasionally occurred in different months across the five-year cycle. This is because the festivals were set according to the solar cycle, whereas the months were set according to the lunar cycle.

Each of the four major Celtic festivals were held at the mid-points between the solstices and equinoxes. For the dedicated, there are two ways to calculate the midpoint. When using the right ascension method, the midpoint occurs at 15 hours or 225o, which corresponds to November 10, 2023. If using degrees of declination, for my latitude and longitude, -16.33o occurs on November 8, 2023. I have opted to split the difference and placed Samhain on November 9th this year.

If you’d like to learn more about the Coligny calendar, let me know in the comments.

Further Reading:

Delamarre, Xavier (2003). Dictionary of the Gallic language: a linguistic approach to continental Old Celtic (2nd ed.). Paris, FR.

Le Contel, Jean-Michel; Verdier, Paul (1997). A Celtic calendar: the Gallic calendar of Coligny. Paris, FR.

MacNeill, Eóin (1928). “On the notation and chronology of the calendar of Coligny”. Ériu. X: 1–67.

McKay, Helen T. (2016). “The Coligny calendar as a Metonic lunar calendar”. Études celtiques. 42: 95–121.

Olmsted, Garrett (1988). The use of ordinal numerals on the Gaulish Coligny calendar. The Journal of Indo-European Studies. Vol. 16. p. 296.

Olmsted, Garrett (1992). The Gaulish calendar: a reconstruction from the bronze fragments from Coligny, with an analysis of its function as a highly accurate lunar-solar predictor, as well as an explanation of its terminology and development. Bonn: R. Habelt.

I believe Robert Graves was actually correct. I’m a fan of Helen McKay as well. If you use the Ogham Year Wheel script for each tree, these align with Ogham on Pictish stones with Ogham. The words for the flowers/buds also align with each rod end, which are for Celtic/Druidic equinoxes and solstices, as well as cross-quarter days where two Pictish rodded symbols are on the same stone. Further, the other symbols on the stones are of constellations visible in the night sky at those times of year. The Ogham script often refers to things like Oak (king), Holly (king), and the correct tree for a Yule log, for corresponding celebrations depicted by the other symbols on the Pictish stones. Rosetta stone examples are Brandsbutt Stone and Logie Elphinstone. These all likely tie in with the Coligny calendar.

All the best cousin,

Tyler Wright

Look at the Pictish Knockando stone “spoked wheel” and tell me that doesn’t look exactly like the Ogham Wheel of the year, complete with the correct divisions…